|

|

|

My Work with the Search and Rescue Man

by Ranger Oakes as told to Harry E. Oakes Jr., Longview, WA

I started in Search and Rescue (SAR) when my handler, Harry, came to the dog pound and saved me from certain death. As a puppy, I thought the life of a search dog would be easy—just sit by the fireplace with a keg of brandy underneath my collar, then go play in the snow. Was I wrong!

First, I had to learn sign and body language, and understand whistle commands. I had to learn to sit, stay, heel, come, and speak on command—then climbing ladders to reach trapped victims, rappelling down cliffs, and swimming in white water!

The most important skills to acquire were tracking and air-scenting, which involved developing my sense of smell. As humans or animals walk, they shed about one thousand cells a day. I know how to smell where they’ve been and which way they’ve traveled. When a person stays in one place, wind and air currents hit them and I can pick up the scent after it’s carried downwind. Heat can dry up the scent, though. That’s why I like to search at night, when it’s cooler, because the scent stays low to the ground and my sinus passages don’t dry out. I have so many more scent-receptor cells than humans, that I can smell hundreds of times better, which makes me highly qualified to locate missing persons.

When trying to find one person among many, I use a scent article, something that belongs to the person that hasn’t been exposed to cigarette smoke or handled by anyone else. Harry places the scent article into a paper sack and introduces it to me. If the scene hasn’t been contaminated too badly, I track by checking out all the smells in the area and eventually find the missing person. I’ve followed uncontaminated scents that were up to three months old. Usually, to be successful, tracking should start within twenty-four hours from the PLS, or “point last seen.”

I’m taught to search in two ways. The first is called general rule-out search, or area search, where Harry tells me to find everyone in an area. We do this if we’re searching at night for plane crash, disaster or avalanche victims. Harry may not know how many are buried under the rubble, so it’s my job to find people, tell him where they are and if they’re alive.

The second way is more specific. When a human is buried under debris, water, snow, mud or dirt, the scent evaporates to the surface and pools there. If the person is alive, I smell this and try to dig them out immediately. If they’re dead, they give off a different scent. When I smell this, I get really upset and paw at the surface very slowly. After the area is cleared of the living, we have the grim job of locating and removing the dead. Sometimes I’m overwhelmed with sadness and so is Harry. We sit, hug each other, and try to make sense of what we’re seeing.

In 1990, the Seattle/King County Disaster Team requested four dog teams for the earthquake in the Philippines. After we arrived, we were loaded onto helicopters and flown into the jungles and mountains. I could see Harry’s concern as we flew over rice paddies and huts; the terrain must have brought back memories of his Army days in Vietnam. Mud and rockslides were everywhere. We saw a place where many buses and cars were buried. I smelled humans under the muck there but had to give Harry the death alert. For days we worked around the clock through terrible conditions: fourteen aftershocks, rock and mud slides, hot weather, snakes and insects. Searching was very difficult when all I smelled was death. In fact, Harry had some of the nurses hide so I could find live victims to cheer me up because I was getting so depressed.

The pain and suffering were getting to Harry. I often heard him praying for the strength and guidance to keep going. God was listening and helped all of our teams pull through that nightmare. We found 59 dead buried in the rubble and helped to treat 289 injured. The death toll went up to sixteen hundred people with thousands of others injured and homeless. The day before leaving, we visited the Filipino Palace and met with then-president, Corazon Aquino. She thanked all of the rescuers and dogs—the first ever allowed into the palace—for our help.

It took Harry quite a while to readjust to the routine at home. We spent a lot of time with each other and Brandon, Harry’s son. An experience like this makes a person, or dog, stop and think. You realize how fragile, yet precious, this existence is.

By the time I left this work, and earth, I’d traveled more than 250,000 miles and put in over 200,000 hours in training, testing and missions. I performed missions in twenty-six states and six countries. I’d found 157 victims on 370 searches and became one of the top SAR dogs in the world. I also accompanied Harry to schools and organizations, helping people to increase their chances of being found if they were ever in an accident or lost in the wilderness. I was given hundreds of awards and was the first SAR dog to win a position in the Oregon Pet Hall of Fame.

When I went over to the other side, Harry said, “I lost my best friend, my partner. The world lost a true hero.”

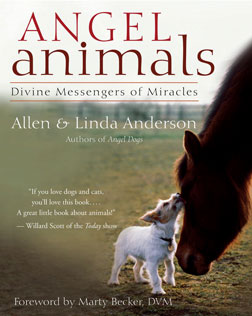

From the book Angel Animals, Divine Messengers of Miracles 1999, 2007 by Allen and Linda Anderson. Reprinted with permission of New World Library, Novato, CA. www.newworldlibrary.com or 800/972-6657 ext. 52.

Allen and Linda Anderson are authors, inspirational speakers and members of the clergy. They co-founded the Angel Animals Network, dedicated to increasing love and respect for all life, one story at a time. Best selling authors of the Angel Animals series of books, they donate a portion of revenue from projects to animal shelters and organizations. Their website is www.angelanimals.net.

|