|

|

|

Reconnecting with the Great Mother

by Riane Eisler

I used to think of the divine as “God.” Now, if I think in terms of a personalized deity at all, I think more of the Goddess than of the God. I feel very strongly that our society’s denial of the feminine aspect of the deity, the Mother aspect, is one of the great obstacles to having that personal relationship, that direct connection with the divine.

In the name of religion we have detoured from the “partnership core” of our spirituality so terribly often. Why? This question was a major motivation for my research into prehistoric Goddess-based partnership societies. To answer it, I had to look at the whole of our history (including our prehistory) and at the whole of humanity.

Born into a Jewish family, my parents kept up religious traditions. My mother baked bread for the Shabbat (Sabbath) and every Shabbat she lit the holiday candles. Now I understand that the role

of the woman in lighting the candles and baking the bread as sacred acts of light-giving and life-nurturing was preserved and honored from when we were still empowered as priestesses and as women to partake directly in the divine, without a male intermediary.

I realized that I didn’t have to go to synagogue or church. Gradually, I tried different things — meditation, fasting. I began to feel that I could establish a direct connection, through my own experiences. Slowly, I also began to understand how, as a woman, I was in a miserable situation if I only have a God who’s a Father, a King, a Lord. It implies that the only relationship I can have with the male deity is indirect. If we as women, are to access the divine in us, then a female deity, a divine Mother, is essential.

For the last five thousand years, society has been oriented primarily toward what I call a dominator model. Because so much of our connection with divinity came through a hierarchy, its institutions and superimpositions interfered with our ability to have a personal relationship with the divine. This religious hierarchy stays in power by disempowering us. Presumably, we cannot have relationship with the deity without somebody (a man) who claims that only he has a real relationship with God and that we can have a relationship only according to his orders.

Through my research in archaeology, myth, and art history, I began to see that it wasn’t always this way. Knowledge of the inherent spirituality of life and of nature came to us very early in our cultural evolution, as early as ten thousand years ago in the Neolithic period, with the first agrarian societies. It’s revealed through the temple models unearthed by UCLA archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, where we see what she calls the “civilization of Old Europe” was a more partnership-oriented society that worshiped the Great Goddess.

In those archaeological remains, we see that the traditional “women’s work” was considered sacred. The temples had pottery kilns and looms for weaving cloth, mortars for grinding wheat and ovens for baking bread, because these were sacred acts. Prehistoric societies saw the living world — the heavens, the earth, everything — as a Great Mother. But though they worshiped the Great Goddess, those societies weren’t matriarchies. She had both divine daughters and divine sons.

In prehistoric societies it was much easier to be connected directly to the divine. Everything was divine, including nature. The Goddess gave life, and at death, life returned to her womb, like the cycles of vegetation, to be reborn. They didn’t have our current artificial distinction between spirituality and nature, with man and the spiritual seen as above woman and nature in the hierarchy.

The human spiritual impulse does not require an intermediary at all, but is inherent in the human condition. When we shifted from the earlier partnership model to the dominator model, we lost our sense of connection. But to have been deprived of that motherly dimension in the deity reflects something in our dominator society: a deadening of empathy, a deadening of caring, a denial of the feminine in men, and a contempt for women and the feminine.

Even though many of us don’t think of spirituality in the context of social systems, we are beginning to recognize that the conquest mentality and the idea of a male God with men made in His image who dominate over women, children, and the rest of nature, could be the swan song for us as a species. The more we move toward a partnership model of society, the more we can search for our higher potential. Humans have the capacity for creativity, for love, for justice, for searching for wisdom and beauty. All these are paths to the divine.

Real love is empathic — an act of service. We must manifest the love of God in action as well as in thought and word. We need greater understanding, but we also need the sacred acts: the sacred act of giving birth, the sacred act of making bread and of sharing that bread. These are all ritual acts in the sense of ritual as an act of love, not as an act of suffering.

Women are taught in patriarchal cultures that they’re supposed to serve. But it’s not enough to honor and to serve others. We also must honor and serve ourselves. We must nurture ourselves. If we become victims and martyrs, we are not serving anyone, because we deny our own divinity and our own worth. Some milestones of my spiritual journey include knowing, and reclaiming, the long-ago traditions when the sacred and the divine had a female form, and knowing that I am not cut off from them because I happen to be a woman.

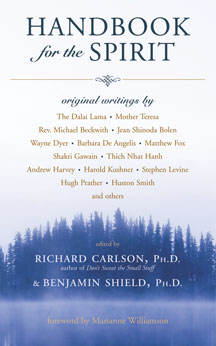

Excerpted with permission from the book Handbook for the Spirit © 2008 by Richard Carlson & Benjamin Shield. Printed with permission of New World Library, Novato, CA. www.newworldlibrary.com or 800-972-6657 ext. 52.

Riane Eisler is an eminent social scientist, attorney, and social activist best known as the author of The Chalice and The Blade: Our History, Our Future. Dr. Eisler is sought after to keynote conferences worldwide. Her website www.rianeeisler.com.

|