Summer 1996: I opened my eyes at the end of my first darshan in India to hear Pujya Swamiji saying, “Yes?” I was the last one in the room, and he addressed me in English: “Yes?” I rose quickly from my place, went in front of him, and bowed low, trying to remember the protocol. Then I sat back on the soles of my feet and saw him looking at me—or, rather, into me— with a love that seemed to permeate every cell of my body and every corner of my psyche. It was not a personal love, not directed at me, but a love so vast and available, it didn’t matter how many others were swimming in it too—there was room for all. “Yes?” he repeated.

“Pujya Swamiji,” I whispered. “Fear runs my life. I have a sense of anxiety all the time, even when I don’t know what I’m afraid of.”

“You fear because you don’t trust,” he said after a brief pause. I thought he would continue, but he didn’t. Just that—lack of trust.

“Really horrible things have happened to me that have made me unable to trust.” And I told him the full story of my twenty five years: childhood sexual abuse and abandonment, struggles with bulimia, for which I was hospitalized several times. It was a story I’d told many times, and it never failed to elicit sympathy, open arms, and praise for how strong I am.

He just looked at me and asked, “Are you going to take this to the grave with you?” Oh, God, no, I thought—of course not.

“Are you going to let it go on your deathbed, just before you die?”

“No, of course,” I replied. “I don’t want to take this unbearable pain to my deathbed,” which was surely six or seven decades away.

“Will you let it go a week before you die, a month before you die?” he continued to ask, never shifting his gaze from its lock on my heart.

“Swamiji, I don’t want to take this to my grave or my deathbed. I don’t want to hold onto it until a week or a month before I die. I want to be free of it as soon as possible.”

He continued to look at me calmly, with neither sympathy nor judgment. Then he said, “You are waiting for someone to come and draw the line for you. You are waiting for someone to come and say, ‘Now you are done.’ But no one will do that. You must draw the line yourself. The choice is yours. You can carry this pain to the grave, you can give it up on your deathbed, you can give it up a week or a month before you die, or you can give it up tonight.”

Tonight? Seriously? I didn’t speak, but he must have heard my thoughts. “Yes, tonight,” he said. “We have a beautiful ceremony at sunset called the aarti. I will tell the priest to give you the oil lamp so you can wave it and pray with it. Then go to Ganga and give her your pain. Take her water in your hands and give it all to her. Just give it to the river. If you give it, she will take it.” He patted me gently on the head as he stood and walked out of the room.

“Just give it to the river?” I wrote over and over in my journal, smiling as I replayed in my mind the swami’s touching yet nonsensical instructions. Fortunately, I was being treated by doctors and psychologists who knew what to do. I wasn’t about to rely on a river to wash away my problems.

Afternoon became evening, and I sat on the cool marble steps lining the banks of the flowing Ganga River. As the final rays of light danced on the waters, the sound of Vedic mantras filled my ears. I stopped giggling long enough to remember my vow from the airplane—to keep my heart open, or leave India.

During the evening light ceremony called the aarti, I allowed myself to be swept away by the song, the music, the fire, the flowers, and the incense. A boy in yellow placed a flaming brass lamp in my hands. “Like this,” he gestured. I faced the river, waving the lamp until my time was up, and the boy took it away.

After the ceremony, as the guests began to disperse, I walked calf-deep into the river. As the chanting dissipated in the background and the flow of the river tried to wrest my feet from its sandy bottom, I entered a silence so deep, it was a place in itself, wrapping me in its arms. In that place of silence, I bent down into the water and carried out Swamiji’s instructions.

I cupped the river’s water in my hands and offered all my pain, all my tears, and all my fear into the water I held in my two hands. “You must forgive him,” Swamiji had said. I stood up to my knees in Mother Ganga until the moon was directly overhead, all the while calling forth every image that had ever caused me pain, that had caused me to dissociate, that had propelled my head into a toilet, vomiting. I recalled countless images that had formed the unbearable background of my life.

Then, in the midst of these images, I saw him—my biological father, Manny— and from this place of imperturbable silence, I saw not a monster but a troubled man who had made mistakes. I saw a man now far away who could no longer harm me, whose life was just as haunted by these choices as mine. And I saw a man who loved me despite his inability to express it. I saw a man I could forgive.

Tears mixed with the water in my hands, and I prayed and cried and prayed and cried, all in silence. These were tears not of yesterday, but of today, tears of release rather than terror, knowing I needed to embrace what is rather than what might have been. I called his image to mind again, stared deeply into my father’s eyes, and said, “I forgive you.” Then I let the water pour from my hands back into the river. “Take the pain,” I prayed. “I give it all to You.”

In the weeks and months that followed, the pain that had coursed through body and mind my entire life lost its grip. The memories were there, no less vivid than before, but I no longer identified with them. They weren’t “me.”

When I spoke to Pujya Swamiji about the miraculous transformation inside me and told him that I no longer felt like the same person who identified with this suffering, he nodded and said, “Once the switch is found and the light is turned on, it no longer matters how dark it had been or where the darkness had come. What matters is that now there is light.”

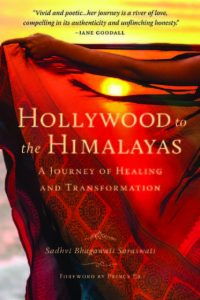

From Hollywood to the Himalayas © 2021 by Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati. Adapted excerpt with permission of Mandala Earth and Insight Editions, L.P.

Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati is a renowned spiritual leader based in Rishikesh, India. She is President of the Divine Shakti Foundation, Secretary- General of the Global Interfaith WASH Alliance and Director of the International Yoga Festival. A graduate of Stanford University, and a PhD in psychology, Sadhviji has lived at Parmarth Niketan Ashram for 25 years where she gives spiritual discourses, teaches meditation, and leads myriad humanitarian programs. Her memoir, HOLLYWOOD TO THE HIMALAYAS: A Journey of Healing and Transformation released August 2021.

Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati is a renowned spiritual leader based in Rishikesh, India. She is President of the Divine Shakti Foundation, Secretary- General of the Global Interfaith WASH Alliance and Director of the International Yoga Festival. A graduate of Stanford University, and a PhD in psychology, Sadhviji has lived at Parmarth Niketan Ashram for 25 years where she gives spiritual discourses, teaches meditation, and leads myriad humanitarian programs. Her memoir, HOLLYWOOD TO THE HIMALAYAS: A Journey of Healing and Transformation released August 2021.