Swimming in a lake, river, or the ocean is completely different from following a black-tiled line back and forth in five feet of water heated to a comfortable temperature in a pool. Open water swimming requires patience, courage, and the ability to adapt to changing conditions. If you’re considering making the jump there are some basic rules to follow to make sure that you have an enjoyable experience.

You need to start by picking the right place to swim. Many bodies of water are not safe for swimming. They may be contaminated with chemicals from street runoff or physical contaminants like jagged metal and broken glass. In many instances lakes, ponds, and streams are homes to predatory animals like crocodiles, alligators, turtles, and large fish. If there are signs posted stating that swimming is prohibited, heed them.

Often you can find city or state parks that have one section of a lake that is roped off with buoys to allow swimming. Sometimes they even have lifeguards on duty. This is a perfect location for your first swim. If a place like this is not available, check with your local triathlon club or masters swim team to find out where they swim.

It’s always best to go swimming with at least one other person, especially if you are going to a more remote location without lifeguards on duty. With that said, here are some other pointers that will help make your first swim a happy and, more importantly, safe one:

1. Check the weather report. There is nothing more frightening then finding yourself in the middle of lake only to have a storm roll over you. Thunder and lightning while swimming is terrifying and dangerous.

2. Tell someone what you are doing. You should specifically tell people where you are going, how long you will be there, and when they can expect you back. If you get stuck, you want to be sure that someone is going to come looking for you.

3. Buy a flotation device designed for open water swimming. This buoy attaches to your ankle by a tether. If you get tired or sick, you hold onto it until you recover, or help arrives. These retail for about $40 and are worth every penny.

4. Acquire yourself a Road ID. If you are incapacitated and someone finds you, the ID will have your name, any health information you deem important, and your emergency contact person.

5. Stay shallow. You want the lake bed to always be a few inches from your fingers. This way if something goes wrong, you can put your feet down immediately. The other benefit of this approach is that deeper waters tend to have more plant growth causing issues.

6. Don’t go for a one-hour, nonstop swim. Break it up into a few short, ten-minute swims. You can set your watch timer to five minutes. Swim out for five minutes, then swim back and rest. Repeat as many times as you like.

7. Find a point on the horizon and practice sight swimming toward it.Unlike pool swimming when you only turn your head to the side to breathe, during open water swimming you need to get used to lifting your head straight up in front of your every five to ten strokes to make sure that you are going in the right direction.

8. Finally, if you get tired, switch it up! Take a break by treading water, floating on your back, using your buoy, or switching to breaststroke, sidestroke, or backstroke. You don’t have to swim freestyle the whole time.

I consider open water swimming a transcendent experience. Combining exercise with the act of communing with nature can be life changing. If you follow these simple rules, you greatly increase the likelihood that your first experience in the open water will be a positive one.

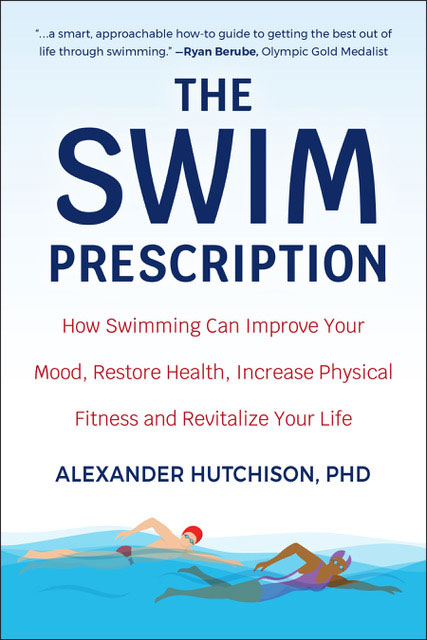

Alexander Hutchison, PhD, is a fitness and wellness expert in Dallas, TX and the owner of The Athlete Company. The Senior Editor for the journal Advanced Biology, he has experience coaching swimming, water polo, triathlon, marathon, and most recently, strength and conditioning. After completing his master’s degree in Kinesiology at Texas A&M University, Alexander was named the head swimming coach at Austin College. He received his doctorate in Exercise Physiology and Immunology at the University of Houston. He reviews for several journals in exercise science, nutrition, and immunology, and is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. He is the author of The Swim Prescription and Exercise Ain’t Enough: HIIT, Honey, and the Hadza.

Alexander Hutchison, PhD, is a fitness and wellness expert in Dallas, TX and the owner of The Athlete Company. The Senior Editor for the journal Advanced Biology, he has experience coaching swimming, water polo, triathlon, marathon, and most recently, strength and conditioning. After completing his master’s degree in Kinesiology at Texas A&M University, Alexander was named the head swimming coach at Austin College. He received his doctorate in Exercise Physiology and Immunology at the University of Houston. He reviews for several journals in exercise science, nutrition, and immunology, and is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. He is the author of The Swim Prescription and Exercise Ain’t Enough: HIIT, Honey, and the Hadza.